Machine me I'm a translator

Let's face it. If you're a translator these days, there are certain things you can't run away from. One is your boyfriend coming to you and proudly telling you that he's having a great time reading the "Game of thrones" book you got him in English, that he just downloaded an automatic translation app that he can use when a specific sentence eludes him and he's on the train to work (i.e. he doesn't have you as his personal human dictionary at hand). Handy for him (and for you too, really, as your own reading isn't interrupted by questions of "what does that word mean?" every other minute). But deep down -as a person whose daily sustenance depends on the act of using your unique (and thoroughly human) brain to coherently assemble in one language a string of words which was originally put together in another language -what you really want to do is bellow a terror-filled "AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAH!!!!" whilst making Vade retro Satanas signs to the man you love.

Of course what I'm getting at here, the thing that YOU dear translator peer, cannot escape, is MACHINE TRANSLATION: a step beyond "computer-assisted translation", not really robots (at least not yet) but nonetheless the definite future of translation -and of just plain communication- in a globalised, stingy economy, which regards human input as expensive bullshit, something which can just be discarded so that the company's numbers can go up.

We all have funny stories of translation gone beserk. There are many blogs, websites and Facebook groups out there (check out Traductions de merde if you're fluent in French) which prove that translation is not just a matter of replacing one word by another and that free machine translation tools are pretty much useless. It takes something that a machine on its own will never have, no matter how much artificial intelligence you give it, and that is skill: the aptitude to identify an issue and to raise a question and then call to mind a number of solutions based on your experience and your knowledge, using your best judgement to make the right choice, taking into account not only language rules and context, but also the time budget you have for your translation. A translator makes such choices every millisecond, anticipating the impact the solution he chooses for that specific word or sentence will have on each and every one of his coming choices, narrowing down the list of possibilities until he can hear the translated text being read out in his head, every word falling perfectly into place, as if that were the only translation possible, and he knew it all along. Translating, to me anyway, often feels like a gigantic game of treasure hunting, a quest where, when you found the graal -i.e. the translation which to you sounds perfect- you feel like a goddess.

But let's be honest: the kind of text we translate or review everyday rarely make us feel like we belong to some Pantheon of language workers. Most of the time, it's more like we're the street sweepers of language, pushing foulness and garbage down the sewage of "globalised communication" (basically a fancy word for allowing merchant A to sell his products not only in consummer-land A but also in consummer-land B, and C, and D, etc.). There lies the difference between a noble and dignified literary translator and a lowly and plain "technical" translator. The other difference is that unless you're a very talented actual writer (for that is what it takes to be a real literary translator), chances are you are not getting any money. I know it for a fact: I tried for a while, realised I was a crap writer, and then I saw where the jobs were and I sold my soul.

Of course I'm being dramatic. I moved "up" now and am not doing as much translation as project leading (which basically involves a lot of fiddling about with recalcitrant translation softwares, soothing moody Project Managers, downloading and uploading material, conjuring up linguistic instructions that will both make the client and the translator happy, writing and reading emails, with the odd translation and proof-reading jobs here and there), but I'm still a dealer of words, and for that I'm thankful. And I really do like my job, in the end. Which is why I'm worried, and feel threatened, by machine translation. Because there's another side to the funny gibberish that comes out of the rear-end of Google translate. I'm really beginning to suspect that these free translation solutions are just baits to make people turn to translation agencies: the sheer unreliability of what they produce makes potential clients realise that if they're even just a bit serious about prospecting on a globalised scale, they need a real translation budget. So they go to translation agencies, and if they're aiming real big they go for the big ones. And what the big ones are doing, is using the good stuff that comes from the technology of machine translation to increase their margins.

For the truth is out there: there are tools which, combining human constructed dictionaries, boolean-type datas, binary code, intricate algorhythms and God knows what else, are actually terrifyingly good. They often need a rapid check -a bit of a past tense here, less of a pronoun here- but are totally understandable (and just as cold and hard as the nail on my big toe, but that's another story). Of course it doesn't work for every type of content (and certainly not for literature), but it DOES WORK. We'd be fools to pretend otherwise. Like a grown adult pressing his hands on his ears, whilst shutting his eyes tight and shouting LALALA at the top of his voice. You don't want to be that person.You need to look the thing in the eye. We, as translators, need to adapt. That is what species do to survive.

Because we're not going to change the way the economy works (and by that I mean that a company, in order to keep employing people, must make profit) our evolution must come from education. There's a lot of client-education to be done, as we have to convince people that what we do is a delicate art which requires proper retribution to be done well, and not something that anyone with a computer can do (it would make a great subject for another post), but we must also re-think the way we teach translation in universities. We need to get to know our enemy. Let's start off by actually telling translation students about post-editing and stop treating it as a taboo. If you're not familiar with the concept, post-editing is the human stage of a real machine translation process, whereby the translator reads and corrects what the machine has come up with. It is fairly new (in that it has been going on for less than a decade I believe) but I was never told about it in school, and I graduated 18 months ago from a nationally recognized translation course. I'm being told that some students in other schools these days are being told by their teachers to tell potential employers that they flat out refuse any post-editing jobs. That's just like shooting a bullet in the head of your carreer as a translator. Honestly, you might as well just go and do something else: there is no way a young and inexperienced translator would enter a translation agency's pool of resources with that attitude, believe me.

Of course post-editing is a task different from that of translation, mainly because you are paid so little for it that you can't afford to spend ages on it and therefore have to make as little changes as possible. And sometimes you lose, and everyone loses, because the machine produced crap, which you spent too much time trying to make better, but without receiving half the money you would have got for it if you'd done the translation in the first place, and the client gets a translation which is ok-ish (but he often doesn't care, and carries on displaying the usual contempt of the business-inclined individuals for the intricacies of language). And sometimes you don't lose as much, because the translation you got was good, you only had to do a bit of fine-tuning, and you managed to balance your time budget -what you have lost is a certain pride in your profession, but that's another story (again).

If we want to be able to be proud to be translators through at least the next 20 years, we need to tell translation students about the different technologies behind machine translation, and start off by teaching them computer programming, for there's a lot of that involved. If we leave it to computer geeks to decide how translation works, no wonder the price to be paid is the quality of language content. That's our area of expertise. I know we are the ones who turned to words in high school in part because we loathed numbers, but we have to make an effort. The only outcome of us not wanting to see the truth and keep fighting those who enforce machine translation upon us is that we'll be left out of the one positive aspect of globalisation for our kind, and that is the intensification of information flows. It's our chance! We need to take hold of it, make machine translation what we want it to be, in order not only to protect ourselves but also protect the integrity of all the languages in the world. We need to accept machine translation, just as we accepted long ago with Internet that the translator in his ivory tower who writes on a typewriter using a paper dictionary and taking all the time he needs just no longer exists.

Just like any other mass production system, translation has become an economy with a high division of labour, whereby the clients hand the work to the agencies, which then appoint Project Managers who dispatch the work onto various resources, each one being assigned a very specific task. Often the freelance translator is at the very bottom of the food chain. And as such, he or she -let's not forget that for many women being a freelance translator is a way to combine holding down a job and being able to go pick up the kids when school is over- is the most likely to disappear completey. Now, I'm not a freelance translator, some of you may even think I've gone over to the Dark side, but I'm still a translator, and as such I know that post-editing is far from satisfying. I just really don't think we ought to fight the tide here, lest we should drown from exhaustion. What we mustn't let happen is for the computers and their programmers to rise on top of the translation hierachy, in a position where they can make the decision of what is acceptable language-wise and price-wise. Because machine translation doesn't necesarly mean there will be less jobs in translation. There will be less jobs for old-school failed-writer type translators (and I don't mean to offense anyone). But if we handle it well, there will be just as many jobs for computer savvy terminologists, people with linguist project-manager profiles, highly specialised translators, reliable reviewers and efficient post-editors. The future of translation belongs to us, the humans. And no, we're not dead.

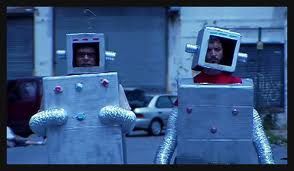

Featured : screen-shot from the Flight of the conchords' song "The humans are dead". And sorry for the bad David Guetta reference in the title. Obviously I was trying hard not to use the F word. And I could translate this article, but it's Saturday I can't be asked, so you'll just have to put it through Google trans. In fact, I'm going to do that right now.